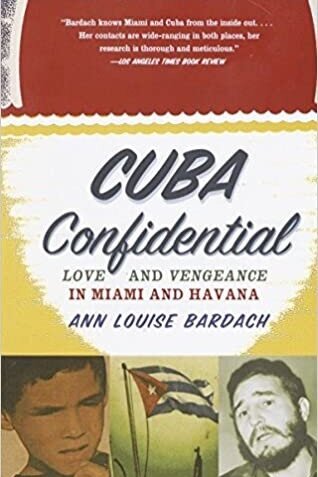

Cuba Confidential

Love and Vengeance in Miami and Havana

Chapter Two Castro Family Values

"One day I'll be out of here and I'll get my son and my honor back - even if the earth should be destroyed.” Fidel Castro in a 1954 letter from prison to his half-sister Lidia.

Some time ago, a Cuban in exile contacted his divorced wife who had left for the United States with their six year old son. He asked that their son be allowed to visit him, arguing that as he was about to undertake a perilous excursion, it may well be the last time for him to see his cherished son. Although his former wife was wary and wounded from a protracted divorce and custody suit, she relented, accepting his promise "as a gentleman," as he put it, to return the boy in two weeks' time.

But when the two weeks elapsed, the boy was not sent home. And two months later, when the father embarked on his dangerous mission, he did not return the son to his mother but rather turned him over to the care of his relatives and close friends. The kidnapped six year old boy was not Elian Gonzalez but six year old Fidelito Castro, the first born son of Fidel Castro by his first wife, Mirta Diaz-Balart. Nor would this be the final round in their bruising custody battle.

For those who were baffled by the passion and tenacity of the battle waged by Fidel Castro for the return of Elian Gonzalez, many of the answers lie in Castro’s own family history. In some respects, for Fidel Castro and many Cubans, the personal is the political. For them, the four decade stalemate between Miami and Havana is the natural outcome of an extended broken family. In certain respects, it is a huge family feud.

The shattered family is manifest in Cuban society from the top to the bottom. Indeed, the Castro-Diaz-Balart relationship can be viewed as the Cuban equivalent of the Hatfields and the McCoys. But in blood ties and political ambition, the relationship withstands analogy to the House of Atreus. Castro sees himself not only as the absolute patriarch of his family but also of his country. In a 1993 interview, when asked what his greatest mistake was, Castro told me, “we may have been guilty of excessive paternalism." But the most tragic casualty of the Cuban Revolution has been the Cuban family. Not unlike the American Civil War, thousands of Cuban families have been riven by politics, geography and conflicting convictions: siblings pitted against each other or their parents or grandparents. And Castro's own family has been no exception.

In 1948, 22 year old Fidel Castro married Mirta Diaz-Balart, an exceedingly pretty philosophy student. The two were introduced by her brother, Rafael Diaz-Balart, who at the time, was one of Castro’s most trusted friends and is today one of his most aggrieved enemies. “Mirta was very beautiful but like a Nordic girl, not the typical Cuban woman,” recalled Max Lesnik, a classmate of both young men at the University of Havana’s law school. “Rafael was very, very close to Fidel Castro. Rafael recognized in Fidel a very important figure but Rafael was also a great speaker and he was a restless man.”

Both were from small towns in Oriente -about a half hour’s drive from each other - and the sons of powerful, strong willed fathers. Diaz-Balart’s father, also named Rafael, was a representative in Cuba’s Congress and the mayor of Banes, a small prosperous town, which was thought of almost as a colony of the United Fruit Company. “Our town was about fifteen blocks long,” said Rafael Diaz-Balart. “My father loved to walk from our house on Cardenas Avenue to the end of town where the headquarters of the United Fruit Company were located.” The elder Diaz-Balart was a friend and close ally of Fulgencio Batista, Cuba’s president in the 1940’s, who hailed from Banes as well.

Castro’s father, Angel, was a guajiro (a country rustic) and self made, who through ceaseless labor became one of the wealthiest latifundistas in the region. “He was very cagey and started out working for United Fruit and then buying land from them,” said a former neighbor. “There used to be a joke among the United Fruit company people that when they all went to bed at night, Angel Castro moved the fence posts to his advantage.” By the time Fidel Castro was born, his father was the lord of Finca Manacas, a sprawling estate in Biran.

Jack Skelly, a neighbor and family friend of the Diaz-Balarts, has known Mirta since he was five years old. “My father was in charge of the railroad for United Fruit which is today Chiquita Banana,” he said, referring to the company then viewed as a symbol of American exploitation of Latin America. “Batista was Banes’ best known citizen, then the Diaz-Balarts. They lived in a company home and paid no rent. It was a big house even by American standards. They were powerful, but they weren’t wealthy. The father was the main lawyer for the United Fruit Company. They were not rich but they had clout. The Castros had a lot of land but they were not a class thing. Fidel’s father made a lot of money.”

“When I came back from the Army in the summer of ’44, Mirta was 15 and suddenly gorgeous,” said Skelly, over coffee at a Denny’s in Ft. Lauderdale. “Dirty blonde with green eyes about 5’7.” And she was the most lovely person. Mirta was el alma de Dios (the soul of God). She was absolutely saintly. Her laugh was sunshine. I still can hear her laughing. And she just loved to dance!”

Rafael Diaz-Balart said that Fidel was not the only friend to whom he introduced his sister. “I had introduced her to a lot of other friends of mine,” he said, somewhat defensively, about his role in bringing the two together. “Mirta was a gorgeous woman, one of the most beautiful at the University. I introduced her also to Rogelio Cequeira, a very handsome engineer, who later became a multimillionaire in Venezuela. But I think she fell in love with Fidel because he was very handsome with many unusual qualities and he had personality. But I believe the main thing she saw in him was someone to challenge our stepmother. Our mother had died when I was 5 years old and she was 28 years old only. It was not a great loss or shock because we had our grandmother, and she lived with us like a mother. My father was a wonderful person but he did not share with us, he was an introvert, and he traveled a lot. And our stepmother, Angelica Franco, was a horrible stepmother.”

Marjorie Skelly Lord, Mirta’s English teacher at the Friends School in Banes - a Quaker school, first met Castro at the Diaz-Balart’s home. “He was a very good looking man,” she said. “And he was very attentive to her but he was indifferent to us. He didn’t like Americans and he hated the United Fruit Company because his father had some bad dealings with them. He had a lot of complexes and always had a chip on his shoulder. I remember once we drove down to the beach and we had to go through some private land and gates which kept the cattle from eating the sugar cane. Well, he didn’t know that and he was giving this big speech in the car about how he objected to the gates.”

Barbara Gordon, whose father was the manager of the United Fruit company in Cuba, was a close friend of Mirta’s and spent time with the young Castro over two summers. “We thought he was a great guy,” she said. “He was very handsome and a very Cuban macho type. He impressed a lot of us, in a teenage kind of fashion as a big guy on campus at the University of Havana. He was a very good friend of Rafael,“ said Gordon who saw similarities between the two young men. “Rafael was also a political guy - believe you me, and I don't think he's above corruption either. A different kind, different degree shall we say. I was crazy about Rafael.”

From the start, Mirta’s parents had doubts about her beau. “Her father was very opposed to him,” said Gordon, ”because he knew what kind of person he was and how he acted at the University and what happened when he visited Colombia (in 1948, Castro attended the Anti-Imperialist Student Congress in Bogota that ended in the Bogotazo riots) and he thought he was a dangerous young man.”

But Castro was a persistent suitor who “kept hammering at the door,” said Gordon. To woo Mirta, Castro stepped into her social world, one very different from his own. “We had dances that rotated at these three clubs - the American Club, the Spanish Club and the Cuban Club,” Gordon reminisced. “Of course, it was all a family affair. Fidel came to the dances but he couldn't dance. I think he would do one trip around the dance floor with Mirta and that would be the end of it. He would end up chatting politics to the men. He didn't like dancing. He loved to talk and he'd go around talking while we were all dancing with Mirta by his side listening.”

Fidel and Mirta married on October 12, 1948 at her family home in Banes. Marjorie Lord attended both the civil and church weddings, as well as a shower given for her at the American Club of the United Fruit Company and the reception at the parents’ house. “It was a very big reception at her parents home,” said Lord, with the house overflowing with people. “I remember seeing Fidel’s mother and brother there. None of us liked Fidel - nor did her parents but they tried to get along.”

Castro had several agendas at the time of his nuptials. One was that he was hiding out from the paramilitary gangster, Rolando Masferrer for killing one of Masferrer’s Tigres at the University. “There were about three groups, and Fidel was in one of them,” said Skelly.

"They were called the Happy Trigger Groups. The man who was in charge of what they called the Banes Barracks sent word to Masferrer that if he put one foot towards Banes he would shoot him on sight. So Masferrer never came to Banes looking for him.”

"Lt. Felipe Mirabal was the chief of the army in Banes," said Rafael Diaz-Balart, “and a close friend of my father.” Following Castro’s wedding to Mirta, it was Mirabal who escorted the young couple to the Camaguey airport to fly off to Miami for their honeymoon. “It was Fidel’s idea because he knew that Masferrer’s people could be waiting to kill him at the airports in Havana or Santiago,” said Rafael. “Because of my father, Lt. Mirabal, and another soldier toting a machine gun,” drove the newly married couple to the airport. “Mirabal could have been dismissed from his military position by consenting to my fathers request,” said Rafael. “And Fidel became very good friends with Lt. Mirabal who became one of the secret service body guards to President Prio and second in command of the Military Intelligence Services. Fidel and I would have lunch with Mirabal regularly at his house in Havana, because his wife Ines was a wonderful cook. Later Fidel would repay him by throwing him in prison for twenty years until he died there.”

Rafael also married around the same time and met up with his sister and brother-in-law in New York. “We then drove to Miami in a car that Fidel bought, a Lincoln Continental from the $20,000 dollars he brought on his honeymoon,” said Rafael. The couple’s extravagant honeymoon in Miami and New York was paid for by Angel Castro and included hotel accommodations at the Waldorf-Astoria. “The money did not come from Batista because Batista was cheap and he gave them a table lamp for their wedding gift,” said Rafael disdainfully. “They stayed in a very luxurious hotel in Miami, where the Shah of Iran would stay. Fidel called me from Miami and told me about it.”

“How she married Fidel is a mystery to all of us,” said Skelly. “A guy who has two left feet and no sense of humor. His whole thing was politics. He wasn’t Cuban because Cubans have an incredible sense of humor. And he didn’t dance or like music and Cubans live for music and dance. And he was a zurdo (klutz).” But few doubted her ardor for him. Some felt that Castro had married up - garnering crucial and tangible benefits for his future. “He’s an opportunist and being married to the sister of the deputy Minister of the Interior was a good move,” observed the late Tad Szulc, Castro’s principal biographer. However, Skelly remembers Mirta as a long suffering spouse. “I don’t think he ever mistreated her,” said Marjorie Skelly Lord, “but he was only interested in politics.”

Back in Havana, the couple settled into an apartment in front of the Tropical Stadium in the Havana suburb of Marianao. Skelly recalled a memorable first meeting with Castro in the summer of ’49. “Mirta was about seven months pregnant and United Fruit had a regular picnic at the beach on the 4th of July,” said Skelly. “It was a full moon night and we had a nine piece combo, Cole Porter songs, down by the beach. And lo and behold who approaches wearing a white guayabera, but Fidel, walking towards me with Mirta. So Mirta came over and gave me a big hug and kiss. And that was my introduction to him. He spent a week at the beach there with us. We had no electricity - just windmills- and running water that you got from the rain, coming in barrels. Every night we played Canasta by Hurricane lights, drank beer, smoked cigars and argued politics. And also dominos. There was a group of eight or ten that gathered in different homes every night on the beach. We laughed a lot. Drank mostly beer really and everybody smoked cigars. Fidel was always yelling and lecturing everybody - although Rafael was right up there with him. Mirta had me looking over her shoulder. We had pretty good puppy love before Fidel. I was what is known as un medionovio - a half of a boyfriend.”

In 1949, the young couple’s son was born and christened Fidel Castro Diaz-Balart, an apellido, last name, soon to become an oxymoron of nomenclature, uniting two warring families in one name. “Mirta was not the type to get involved in her husband’s affairs; she was a homemaker,” said Lesnik. “I remember we used to go to the Orthodox Party meetings when Fidel was campaigning for representative. Fidel was traveling throughout the provinces, speaking at meetings and Mirta would remain in the car alone, sleeping, and waiting for him to finish. Everyone says that Rafael was always a Batistiano, but I remember when he was in the Orthodox Party with myself and Fidel,” said Lesnik. “He switched in 1949 when Batista named him the head of his Youth Party.”

Rafael Diaz-Balart had tried to forge an alliance between his ambitious brother-in-law and Batista, arranging a meeting at Batista’s palatial estate, Finca Kuquine, famous for its solid gold telephone, a gift from the American Telephone and Telegraph company. “Fidel told Batista that he should implement a coup at that time,” said Diaz-Balart. “He said that (President Carlos) Prio was ready to flee the country and Batista should make his move immediately. I also remember that he looked over the books in Batista’s library and said to him, ‘you have many books here but you don’t have a very important book, Curzio Malaparte’s, The Technique of the Coup D’etat.’ He said, I’ll send you a copy,’ and Batista broke with laughter. He loved to laugh.”

In the Spring of 1952, Castro was a candidate for representative for the Orthodox Party in the upcoming election. But his dream of winning a seat, as well as the dream of democracy for Cuba was shattered, when Batista seized control of the country with a military coup on March 10, 1952. The historian Hugh Thomas likened the impact of Batista’s treachery on Cuba to an individual struck by a “a nervous breakdown after years of chronic illness.” Although well received by the U.S., which saw Batista as a reliable ally to safeguard its interests, Cuba’s intelligentsia and democracy proponents were shattered.

The Diaz-Balarts, however, emerged as winners and their friendship and loyalty to Batista was well rewarded. “The Diaz-Balart family were always batistianos,” said Juanita Castro, Fidel’s younger sister, with undisguised contempt. “Rafael ran Batista’s Ministry of Interior and Batista created a ministry - secretary of communications and transportation - for Rafael’s father.” The powerful Interior Ministry, sort of a Cuban amalgam of the FBI and CIA, included Batista’s dreaded secret police and was charged with maintaining “public order.”

Barbara Gordon visited her old friend Mirta in August, 1952. “They had a funny little apartment in Marianao,” recalled Gordon. “Rafael took me around in his car and he was carrying a gun in the car. He was with Batista by then and Fidel was already a guerrilla. Fidelito was still crawling,” she said. “I remember I was sort of horrified by the way she was living. I said I want to see Fidel and she said, ‘he’s gonna drive by and wave at you.’ And he did. He waved and that was it. She was separated from her family because she didn’t think that Batista should have come back and was very supportive of Fidel.”

Four years later, on July 26, 1953, Castro declared war on Batista - and his in-laws - with an audacious and disastrous attack on the Moncada military garrison in Santiago. Castro believed that if he seized control of the garrison, he could arm his civilian supporters in Santiago as well as capture the backing of many in Batista’s army. A week before the assault, Castro had stopped by to visit his brother-in-law Rafael at his office in the Ministry of Interior to suss out whether the police were wise to his plans. Castro left confident that word had not leaked out. Nevertheless his grand assault was doomed. Outnumbered ten to one by Batista’s soldiers, thirty one of Castro’s 134 guerrillas were captured and killed, some of them brutally tortured.

Luis Ortega, the editor of La Prensa, didn’t think that the attack on the military garrison was as hare-brained as many thought. “He attacked the Moncada because he had the idea that if he took control of Santiago, he could spread the revolution to the rest of the country. He was not crazy. It was not the first time that someone had attacked the Moncada. Nationalism is the most important aspect of Castro, that and his opposition to the United States. Before, Cuba was like a state of the United States. I believe that he liberated the country from the United States at a high cost. Too high. But he has profound roots in the Cuban history.” Castro also had a profound appreciation for Cuban memory. Jose Marti, the revered poet, muse, and champion of Cuban independence was born 100 years earlier in 1853, and the fidelistas took to calling themselves the “Generation of 100 Years.”

Fidel and his brother were among those who emerged unscathed - in no small part owing to the influence of his wife’s powerful family. Certainly, Castro owed his life to his father’s good friend, Archbishop Perez Serantes, who negotiated his surrender after the catastrophic assault. But according to one Diaz-Balart relation, family ties also played a role in keeping the young revolutionary and his brother alive. “One reason Fidel was not tortured and killed after Moncada was because my cousin’s husband, who became the patriarch of the Diaz-Balart cousins, paid off the guards. So much for ideology.” But Rafael Diaz-Balart said neither he nor his father gave any special treatment to their revolutionary in-law. “I never saved his life in prison,” he said. “Those are stories. We saved his life when he married my sister because my father asked Mirabal to do him a favor - that one time only.”

However, most observers from that period agree with Gordon's appraisal. “He never would have got out of prison alive if it had not been for the Diaz-Balart family,” she said. They also noted that the tug-of-war between the Castros and Diaz-Balart had taken a toll on young Fidelito. Castro's confidante, the writer, Luis Conte Aguero recalled the precocious young Fidelito saying, " When Batista falls, my dad is going to cut off the heads of the batistianos, except for my uncle and grandfather because they are good."

The Moncada assault made Castro a national hero, a stature that bloomed exponentially during his trial, in which he defended himself and gave his famous oration “History will absolve me.” But it was also an irreparable wounding to his wife’s family - from which bad blood has flowed ceaselessly ever since. Castro was now directly at odds with his brother-in-law, who felt conflicted by a need to protect his only sister and by his rage against his ungrateful brother-in-law. Rafael Diaz-Balart got one measure of revenge when Castro and his brother Raul were sentenced to 15 years in prison on Isla de Pinos. But more was to come.

Castro had been conducting a relationship with a stunning, green-eyed beauty named Natalia Revuelta known as Naty. Revuelta, a wealthy married socialite turned revolutionary, offered her Miramar mansion to Castro and his conspirators and was a valiant and reliable courier during the plotting of the Moncada assault. Her ardor for him was unabated throughout his imprisonment. Indeed, the wily Castro had both his wife and Naty running operations for him. Lesnik remembers that “a friend of mine, using my car, took Mirta to the airport to fly to Isla de Pinos to see Fidel and get this very important document he had written in prison. Mirta smuggled it out of the jail in her bra. She took it to this lawyer belonging to the Orthodox Party named Jose Manuel Gutierrez. That document, which Castro called ‘History Will Absolve Me,’ was rewritten by the great Cuban intellectual, Jorge Manach and became the Manifesto of the 26 of July Revolution. “

In Castro, Naty had found the ideal antidote for her ennui with society life, her marriage to a doctor named Orlando Fernandez, and motherhood. “Naty was raised to marry well. She had gone to prep school in Philadelphia and then went to the equivalent of a finishing school,” said her biographer Wendy Gimbel. “When Fidel met Naty she looked like a movie star who had been dipped by the gods into a golden oil like Ava Gardner and Rita Hayworth. She had wide green eyes and a beautiful mouth and raven hair. She always juxtaposed herself against Mirta. She was the cosmopolitan, well traveled, educated woman, and Mirta was a provincial little girl with no sort of worldliness to her. Part of Naty’s self vindication was her belief that Mirta was incapable of being the kind of wife that a young revolutionary leader needed.”

Salvador Lew, a lawyer who became head of Radio Marti in 2001, was close to both men at the University, and remembered vividly the escalating drama between the two families. “Mirta loved Fidel very much but Rafael never liked that marriage and he was always pushing for their break up. As the deputy head of the Ministry of Interior in Cuba when Fidel was in jail, he could see their correspondence because all prison mail was censored. And he got a letter for Naty and put it in the envelope for Mirta. And he put Mirta's letter in the envelope to Naty. Of course, Mirta was very hurt when she read the letter that Fidel wrote to Naty. That was the key to the whole divorce. She wouldn't have left the marriage except for the letter Castro wrote to Naty.” A humiliated Mirta phoned Naty to inform her of the letter she had received and request her own letter which Naty claimed not to have opened. Although some biographers have attributed the letter exchange to a mid -level clerical mistake, Lesnik and Juanita Castro concur with Lew’s version that there was nothing accidental about the letter mix up. Certainly, Mirta came to resent her brother’s role. “Mirta and Rafael are not on great terms at all,” said Gordon, who traced the breach back to their differences over Castro.

While Mirta was devastated by the letter mix up, Naty was hopeful that it would enliven her prospects to succeed Mirta. “Naty said that Mirta called her up and accused her of all manner of things,” explained Gimbel. “At one point, she thought maybe the prison censor was responsible, but the censor had been so kind to them previously that she doubted it. So she became suspicious of Mirta’s family’s role.” The final blow to the marriage was Castro’s discovery in prison that the Diaz-Balarts had put Mirta on the government payroll, which Castro saw as an irrevocable affront to his honor. "Tell Rafael that I am going to kill him myself," a fuming Castro told a journalist friend at the time.

In July, 1954, Mirta Diaz-Balart announced that she wanted a divorce from her husband and soon left for the United States with their five year old son, Fidelito. Learning that his child had been taken to the land of Yankee imperialism, and the backers of Batista and his hated in-laws, Castro flew into a rage: “I refuse even to think that my son may sleep a single night under the same roof sheltering my most repulsive enemies and receive on his innocent cheeks the kisses of those miserable Judases," Castro wrote his older sister Lidia in 1954. "To take this child away from me….They would have to kill me…I lose my head when I think about these things." Should the courts rule against him, he vowed “to fight until death…” Castro, facing a long prison term, was hardly in a position to be issuing orders much less making unprecedented paternity demands. But he did just that. Instructing his lawyers to seek custody of his son, he flat out refused his wife a divorce unless Fidelito was returned and enrolled in a school in Havana.

By year’s end, however, Castro had lost the first battle. Mirta got her divorce and retained custody. Castro fumed in his letters to his sister. "One day I'll be out of here and I'll get my son and my honor back - even if the earth should be destroyed in the process…I don’t give a tinker’s damn if this suit lasts until the end of time. If they think they can wear me down and that I'll give up the fight, they're going to find out …that I'm disposed to reenact the famous Hundred Years War. And I'll win it." And he did just that.

Fidel Castro’s prison letters leave no doubt that he was and is a scorched-earth warrior. Indeed, his belligerent intractability is a point of honor. In another letter, he boasted of being "a man of iron," then reminded his sister that "you know I have a steel heart. And I shall be dignified until the last day of my life.”

Castro and his brother were sprung from jail in 1955 after Batista made the mistake of his life and granted a general amnesty to political prisoners. Castro stayed briefly in Havana where he threw himself into reorganizing his followers and mulled over the possibility of running for mayor of Havana. But fearing for his life, he fled to Mexico in July 1955. There he relentlessly plotted two dual strategies: his triumphant return to Cuba and getting custody of his cherished son “by any means necessary.” In the end, he negotiated custody of Fidelito for himself for one month of every year.

With her son in tow and her divorce final, Mirta moved to Ft. Lauderdale. “We got her and Fidelito an apartment about a block from my father’s,” said Jack Skelly. “She spent a lot of time with us. Every Sunday, she would cook a meal for my mother. This is where our medionovio started up again. But she was also a very good Catholic. I should have married her.” His sister Marjorie recalls this period as being a “very tough time for Mirta. She lived alone in an apartment with Fidelito. My mother would babysit for her sometimes.” She recalls that Mirta held down two job, one hostessing at Creighton’s Restaurant, an upscale eatery in Ft. Lauderdale, and teaching part time at a private school.” In 1956, Mirta abruptly decided to return to Cuba.

Within the year Mirta met and married Emilio Nunez Blanco, the son of Batista’s ambassador to the U.N. The new family went to New York where Fidelito attended school in Queens. Again, it seemed that Mirta had gained the upper hand. But not for long.

In 1999, Castro described Elian Gonzalez's situation as a "kidnapping" and an "abduction." Again, there are personal parallels. In September, 1956, Castro placed an arranged phone call from Mexico to his ex-wife at the office of his father-in-law, then Batista’s Minister of Communications. Present for the speakerphone conversation was Mirta, her brother, Rafael, their father and Mirta’s new husband. The estranged couple agreed to a fifteen day visit for Fidelito with his father, the dates of which coincided with Mirta’s honeymoon to Paris with her husband. Castro would send his sister Lidia to Havana who would pick up Fidelito and travel with him to Mexico and return him two weeks later. Instead, Castro promptly installed his son in the walled Mexico City mansion of a former Cuban singer named Orquidea Pino and her wealthy Mexican husband, his allies and patrons. One month, two months went by without Fidelito’s return.

In what amounted to a will, Castro bequeathed his son to the couple, in the event of his death. Using arguments not unlike those that Elian's relatives would employ 45 years later, Castro wrote that “because my wife has proven to be incapable of breaking away from the influence of her family, my son could be educated with the detestable ideas that I now fight…I am leaving him with those who can give him a better education, to a good and generous couple who have been, as well, our best friends in exile… And I leave my son also to Mexico, to grow and be educated here in this free and hospitable land…He should not return to Cuba until it is free or he can fight for its freedom.” Castro defended his actions in a November 24, 1956 letter to the couple, writing that “I am making this decision because I do not want, in my absence, to see my son Fidelito fall into the hands of my most ferocious enemies and detractors, who in an extreme act of villainy…outraged my home and sacrificed it to the blood tyranny they serve.” Castro protested disingenuously that he had not acted out of anger but in his son’s best interests: “I do not make this decision through resentment of any kind, but only thinking of my son's future."

With that, Castro and his barbudos- bearded followers- sailed back to Cuba on the catastrophically overburdened Granma to burrow themselves in the Sierra Maestra mountain range above Santiago from where Castro would wage his guerrilla war. A distraught Mirta repeatedly called Lidia concerning the boy’s whereabouts. Rafael Diaz-Balart recalled the traumatic event. “Lidia told Mirta, ’I’m really sorry but Fidel says that the boy cannot be sent home to you because your family are batistianos.‘ Mirta became hysterical. She came to see me and we prepared a trip with her husband Emilio who was quite helpful. Mirta with Emilio went with two of my men from the secret police and an arrangement was made for Mexican policemen to be with my people during the operation. We figured out that Fidelito and Lidia were staying at Orquidea Pino’s house near Chapultepec Park. We had two cars at opposite ends of the street: in one car was Mirta with Emilio, the Mexican policemen and my men. We were lucky it was daytime because Mirta was able to spot the child in the car with Lidia, when it drove up with Castro’s militia men. We followed them into a busy street and Mirta’s car was able to pull up right next to the car. Immediately we jumped from our cars and the Mexican police aimed their firearms towards Castro’s armed men. Fidelito saw his mother, and ran directly towards her.”

When Emma Castro, Castro’s younger sister who lived in Mexico, protested to the police that the men had “seized my nephew,” the Cuban Foreign Minister responded coolly that “the child is with his mother which excludes the possibility of a kidnapping.”

Two years later, when Castro toppled Batista, he promptly took charge of his son. Salvador Lew was on the plane that brought Fidelito and dozens of jubilant exiles waiting out the war in New York back to Havana on January 6, 1959. The plane was delayed 12 hours because of poor weather. On the plane, Fidelito was playing with the son of Raul Chibas, Eddie Chibas’s brother, who had backed Castro after his brother’s death. “They were having a very adult conversation,” said Lew. “They were joking about Ventura, the police chief who had tortured Chibas.”

A patient Mirta waited at Havana’s Jose Marti airport for her son, but it was Castro who would be calling the shots from the minute their son stepped off the plane. Two days later, Fidelito accompanied his father atop a Sherman tank for his triumphant march through Havana to the cheers of a million Cubans. Mirta watched the event on television at her home in Tarara Beach, outside of Havana. She was now married with two young daughters. An old friend of Mirta’s, who requested anonymity, was also at her house watching the great event. “Fidel was atop this Sherman tank with Huber Matos and Fidelito,” he said. “Mirta had a group of six, eight friends over and we were watching it on live TV and Mirta said, ‘Ah, poor Cuba. If he's as good a leader as he was a father, then poor Cuba!’ That's what she said because he was a terrible father and husband.”

As Cuba’s maximo lider, Castro reversed her custody order and refused to allow Fidelito to leave with her. Mirta remained in Cuba for another eight years. “She had hated her stepmother so much that she didn’t want Fidelito to go through the same thing,” said Gordon. “She wasn’t going to leave the country and let her son disappear. There was a mutual agreement that she would stay. I asked her, ‘what does Fidel do with Fidelito?’ And she said he would send the car every so often and take him out to baseball games and things like that.” Later Fidelito would attend school in the Soviet Union, earn a doctorate degree in physics, and marry a Russian woman. Today, he lives with his second wife, the daughter of the Cuban General German Barreiro (the former chief of Cuban counter intelligence who fell into disgrace with a political scandal in 1989), and three children in Havana.

In early 1959, Castro gave a television interview to Edward R. Murrow for his Person to Person series from his suite at the Habana Libre Hotel, (which a month earlier had been the famous Havana Hilton). Turned out in stylish white pajamas, Castro spoke in strained but understandable English. Asked if would soon cut his beard, the guerrilla leader seemed bemused, and responded, “When we fulfill our promise of good government, I will cut my beard.” Then he summoned his son to join him. The fair-haired Fidelito, clutching a black labrador puppy, and looking not unlike the 1950’s American television child character Wally Beaver, rushed on camera to kiss his adoring father. “Hello, Fidel, Jr,” boomed Murrow, “is that your puppy?” Speaking as fluently as a kid in a Philadelphia playground, Fidelito, grinned winningly and responded, “No. Someone gave it to my father as a present.”

Not long after, Castro was being interviewed on Meet the Press in Havana when he learned that Fidelito had been in a very serious automobile accident and was rushed to the hospital. Jack Skelly recalled the events vividly. “The TV moderator said ‘Comandante, thank you for your time tonight, but we understand that you will want to go to the hospital.’ And he said, ‘no, no’ and Fidelito was almost dying. I went to the hospital. His brother Raul was there with Mirta. Raul was the one that came to comfort her.”

By all reports, Fidelito, who has his mother’s light eyes and his father’s visage and beard, is said to be a thoughtful man, a devoted father and a less devoted husband who enjoys Havana’s disco scene. Mirta has lived in Madrid with her second husband and two grown daughters since the mid-‘60’s. In late 2001, Mirta told friends that she had filed for divorce. “It was a very sad marriage,” said Skelly. “Emilio is a very jealous, possessive guy. She has had terrible luck with men.” Mirta has resumed her relationships with the Castro family in Cuba, notably with Raul Castro. She has never spoken publicly about her former husband.

For years, Mirta would visit with her son in Europe - on his various trips to conferences in Belgium, Geneva, Amsterdam and in Madrid. Barbara Gordon, however, saw Mirta in 2000 in Madrid at a time when she had not seen her son for about eight years.

In the early 1990’s, Fidelito was dismissed from his job running Cuba’s atomic power industry and supervising the now defunct nuclear reactor in Cienfuegos amid a corruption scandal. Gordon and Rafael Diaz-Balart believe that Fidelito was put under house arrest for a period - a charge denied by the Cuban government. But, he was indisputably en desgracia for an extended period, during which time, his relations with his father were frosty. “Mirta worried about when she would see him again and she did not look well but gave the impression of being very fraught with worry,” said Gordon. Fidelito resumed his duties in full in late 2000, although the nuclear reactor remains mothballed.

Mirta's nephew, Lincoln Diaz-Balart, born five years after his cousin Fidelito, would become the first Cuban-American member of the U.S. House of Representatives. His brother Mario is an outspoken Republican state senator who headed up the Florida Legislature’s redistricting committee in 2001. Lincoln is among Castro's most implacable and bellicose enemies and led the crusade to keep Elian Gonzalez in the U.S. During his political career, he has called for a naval blockade of Cuba and military force to be used against his former uncle. In a stunning but seemingly unconscious parallel, Lincoln Diaz-Balart gave Elian Gonzalez a black labrador puppy soon after his Miami relatives laid claim to him. “What's happening today with Rafael and Lincoln and Fidel is a family quarrel,” observed Lesnik, who favors negotiations with Cuba. “It has less to do with ideology than opportunism. It is a nasty family quarrel in a divided family.”

**

It was in the Sierra Maestra in February 1956, that Castro met the most significant woman, and arguably person, in his life. Celia Sanchez, a doctor’s daughter from Manzanillo, was already a committed revolutionary with an impressive and courageous track record. At 36, she was six years Castro’s senior, dark haired, dark eyed, flinty and lean in an attractive way. She was a natural strategist of incisive intellect with unstinting devotion to Castro and the revolution. Like Castro, she was forged out of waging battle, and she soon became his comrade, lover and confidant.

“I’d say Celia Sanchez was the great love of his life,” said Tad Szulc, who spent cnsiderable time with Castro and his inner circle. “Celia was the only person in my experience who had any kind of sway over Fidel, the only person who could say ‘you’re full of it and you shouldn’t be doing this.’ I went to their hideout at the top of the Sierra Maestra with some of his close friends and they showed me the bed - a double chain bed -and the desk where she worked. This was their way of saying that they were everything to each other. She ran the logistics of his whole operation, and then when they came down to Havana, she was absolutely vital to him.”

Huber Matos, an early revolutionary hero, was introduced to Castro through Sanchez. “She was a Catholic activist. We were friends from long before Fidel appeared in the scene. We belonged to the Orthodox party that Eddy Chibas headed. Her father lived in El Pilon in the south of Oriente. We had been together in another conspiracy in 1952 after Batista’s coup. After the Moncada assault, she told me “We have to join these people.” Celia had already organized a 26 of July cell and the majority of the boys in it had been students of mine. She even came to my house in Yara with some of those boys to see if she could talk me into joining the 26 of July Movement. I committed myself to help. I gave them a rifle and I told them they could discreetly practice shooting in a small farm that we had. She asked me for some money which I gave to her, not very much. When I arrived in the Sierras, she had become a very important person. Neither of them told me they were lovers, but I spent some nights in the hideout where they lived. Fidel had a hammock and Celia had a big bed. Fidel would sleep with me on the floor, all night telling me stories. Celia had great influence over Fidel. I never saw them argue. Many times she would say, ‘Fidel you have to do this and that,’ but she wan’t ordering him about. Celia was a woman of character who was almost religious in her dedication. She wore a little chain around her ankle. She was easy going, very loyal to her friends. She was a full-time guerrilla fighter who had realized herself in the struggle.”

After the Revolution, Celia’s apartment on Calle 11 in Vedado became Castro’s second, often his first home. “I think Celia’s death from lung cancer in 1980 was probably the most tragic loss in his life,” said Szulc. “She smoked Camels like a chimney, just like he used to.“ Celia’s house served as an auxiliary headquarters for Castro where she often cooked his meals and watched over his food. She even set up a dentist’s chair for Fidel to have his teeth fixed at her house.

Lee Lockwood, a former LIFE reporter, who traveled with Castro in the early 1960’s said her death marked the end of an era. “She and Rene Vallejo (Castro’s doctor and close friend who died in 1967) were the two most important people of his life,” he said, but Celia was the most important. Interestingly, both Vallejo and Sanchez were adherents of Santeria, the syncretic Afro-Cuban religion of the country and both were believed to be santeros. While Castro cracked down hard on the Catholic Church, he adopted a laissez-faire attitude towards Santeria, and even dabbled himself.

When Lockwood visited Castro at his home in Isla de los Pinos and again in Pinar del Rio, Sanchez and Castro “would return to their room together after dinner. She had no ego and he is all ego, so that was the key. He trusted her totally. She was a warm person, funny person, tough Orientale. She was attractive, in kind of a tough stringy way - not voluptuous or sexually noticeable. In the Sierras, she was indispensable, and when they got to Havana, she ran interference, she was a troubleshooter, the resolver. Her answering machine announcement, and three or four million people had her private number - gave you this long message - giving tips for just about everything imaginable.” And she was much more worldly than Fidel. She had homosexual friends for example, painters, artist friends.”

But Sanchez was careful about whom she allied herself with. After the Revolution, Huber Matos, feeling that Castro had betrayed its original ideals, sent a letter of resignation. Castro went into a rage and had Matos tried for treason and sentenced to 20 years in jail. “I was always treated very well by Celia, until I fell in disgrace,” said Matos. When that happened I didn’t hear from her anymore. I imagine that her loyalty to Fidel would make her swallow whatever affection might be between us. Before I fell in disgrace, she knew from Fidel about my situation and my incompatibility with the leadership. She subordinated everything to her unconditional loyalty to Fidel, even abandoning her Catholicism and her convictions as a person. I imagine that before she died she must have felt a little frustrated and sorry about her role.”

"Cuba has never been the same since Celia died," said Alfredo Guevara, Castro’s closest friend going back to their university days. "She kept Fidel in touch with the people. She was a 1000 times more effective than any intelligence organization and she was one of the few people who could tell Fidel news he didn't want to hear.” When I asked Castro about Sanchez, he betrayed little emotion and responded with the formality of an eulogy. "She was like a guardian angel for all the revolutionary fighters whose problems she took care of. She died prematurely,” he paused, “so she never knew these difficult times," referring to the early 1990’s after Cuba lost its Russian patron.

Celia Sanchez was undoubtedly aware that Castro had his share of paramours. As his grip on his island tightened, Castro assumed more and more of the role of the Cuban Romeo - albeit in his own discreet fashion. Unlike many in his inner circle, he loathes pornography and discourages its circulation in Cuba. Despite the multiplicity of his conquests, said to include the Italian film siren Gina Lollabrigada, Castro seems to have engendered loyalty and discretion among them. Never have tawdry photographs or tell-all memoirs surfaced about Castro. Like many Cuban men, he is a dedicated womanizer but he does not take chances. Any woman who captures his fancy is first checked out by seguridad to ensure that she is not a CIA plant. After her screening, unbeknownst to her, a third party would invite her on an excursion such as a picnic or reception at which point Castro would make his move.

Graciela, who now lives in Miami and requested anonymity, said she began seeing Castro in 1963 when she was a teenager, although she hastens to add, “at 14, I looked 18 and was already working as a dancer at the Tropicana.” She said introductions were done by Castro’s close aide Jose Abrantes whom she said was designated to handle the delicate negotiations between Castro and women. Graciela began her three year affair with Castro when she was 16 and said that most of their trysts took place at his suite at the Habana Libre. She remembered him “as the most tender of lovers,” and said she was deeply in love with him. Beside his bed, she said, was a book that keenly engaged him at the time, The Psychology of the Masses written by Gustavo Le Bon. She recalled with amusement how on one occasion in the mid-‘60’s she stepped out on the balcony of his suite with him overlooking the Malecon. “Fidel was looking down at the hundreds of people below strolling and milling about and he said to me, ‘One day very soon, Graciela, every Cuban will have a car!’” She laughed. “And they still don’t have bicycles.”

Marita Lorenz, another of Castro’s conquests, is one of the few who has sought to promote and profit from a fling with Fidel Castro. Lorenz claims that after Castro spurned her, she turned CIA operative and would-be Castro assassin. Having first met Castro in 1958, when her father’s ship docked in Havana harbor, Lorenz claimed she returned to Havana in 1960 to kill her former lover. Although she says she was spurred on by his rejection of her after she became pregnant, there is ample evidence that an aide of Castro’s was the actual father of her terminated pregnancy.

Lorenz offered a dramatic account of one of her counter-revolutionary capers -that is backed in part by other CIA operatives of the time. “I was given two botulism toxin pills that looked like white gelatin capsules to drop in Castro's drink. Just one would do the trick, I was told, killing within thirty seconds. When you swallow it, right away your throat would be paralyzed. You can't even scream…. I knew the minute I saw the outline of Havana I couldn't do it. Too many memories. I hopped in a jeep and went to the Hilton. Just simply walked in, said `hi' to the personnel at the desk, went upstairs to the suite. Room 2048. I went in and waited. I was scared to death. I had stashed the capsules in a jar of cold cream. And when I looked for them, they were all gunked up. I fished them out and flushed them down the bidet even before Fidel got to the room. ‘Why did I leave so suddenly,’ was his first question, then ‘Are you running around with those counter-revolutionaries in Miami?' I said yes. I tried to play it cool. The most nervous I have ever been was in that room because I had agents on standby and I had to watch my timing. I had enough hours to stay with him, order a meal, kill him and prevent him from making a speech that night which was already announced. He was very tired and wanted to sleep... He was chewing a cigar and he laid down on the bed and said, `did you come here to kill me?' Just like that. I was standing at the edge of the bed. I said, `Yes. I wanted to see you.' Then he leaned over, with his eyes closed, and pulled out his .45 and handed it to me. A beautiful hand carved gun with a pearl handle. I flipped the chamber out and hit it back. He didn't even flinch. And he said, ‘You can't kill me. Nobody can kill me.’ And he kind of smiled and chewed on his cigar.”

Following the Revolution, Naty Revuelta sought to renew her relationship with Castro, but with little success. Notwithstanding Reveuelta’s considerable allure and usefulness, her dream of succeeding Mirta was never realized. “She was useful while he was in jail because she got him books, and because she was beautiful, and she could be a fantasy for a moment,” said Gimbel. “But by the time he got out of jail, he didn’t really care about her. He was in the business of revolution. Celia was the most important. Naty and the others had walk-on parts.”

However, Naty continued to see him during his three month stay in Havana in 1956 before he fled to Mexico. And it was during one of these rendezvous - at his sister Lidia’s Vedado apartment, that Naty said that her daughter Alina was conceived. The Castro family has harbored some doubts about Alina’s paternity but Castro saw to it that Naty and her family were provided for – perhaps not in the manner she was accustomed to, but the basics were provided. “Castro chose to behave decently to her later,” said Szulc, seeing to it she had a good car, not a Cuban Lada and that she kept her beautiful house. Gimbel disagrees. “I don’t think Castro looks after her at all. If she were down and out, he probably would take care of her. Naty is a real survivor. It helped having Alina as her daughter.”

According to a memoir penned by Alina Fernandez, there was persistent tension between Naty and Celia. On more than one occasion Celia “met with Alina [who led a troubled life in Cuba including four marriages] and tried to straighten her out,” said Gimbel. Alina was not appreciative and would refer to Celia as La Venenosa (the poisonous one) and “Fidel’s personal witchcraft counselor.” The latter was no doubt a reference to Sanchez’s lifelong interest in Santeria. But it is difficult to find anyone -on either side of the political divide- who didn’t respect Celia Sanchez, who was capable of coping with Castro’s infidelity and subsume her own romantic ambitions. “It was a bit of a class war. Women like Celia and Haydee [Santamaria, another guerrilla leader] viewed Naty as a country club socialite who happened to sleep with Castro. And she looked down on them as guajiras. They felt that they had risked their lives and essentially that Naty had changed her clothes.”

With her privileges and ability to travel Naty Revuelta has had countless opportunities to defect. She has chosen to remain in Havana, and notwithstanding difficult times and a recent bout of illness, seems to be without bitterness. She can often be found at parties at the elegant residence of the head of the U.S. Interests Section, holding court. “Naty was part of history from her own point of view. And she had a good part,” reasons Gimbel. “If she left, she’d just be another middle class person in Miami.”

In the early 1990’s, word began to seep out that Castro had married a second woman, Dalia Soto del Valle, a beauty from the southern port city of Trinidad before 1970. The couple have five grown sons, all curiously given names beginning with the letter A: Angel, Antonio, Alejandro, Alexander, and Alexis. But unlike her predecessor, Soto del Valle has never been publicly acknowledged as Castro’s wife nor is she seen at official functions by his side. (Days after I wrote about their peculiarly distant lifestyle in a national magazine in July 2001, Cuba television beelined on Dalia at a public reception for several minutes, as if to announce her to the world.) But the same ideological schism that has divided the Diaz-Balarts runs through Soto del Valle’s extended family. She has a cousin and a granddaughter living in Miami and, according to a memoir of a political prisoner, Dalia's father, Fernando Soto del Valle, penned a lengthy letter – that in, in essence was a political screed filled with fury and despair at his son-in-law. Although it is clear that Dalia’s father, who died a decade ago, was deeply embittered by Castro, the letter has questionable authenticity.

There are two versions as to how Castro met Dalia. Former guerrilla leader Lazaro Asencio ties the meeting of the two to the disappearance of the beloved revolutionary idol, Camilo Cienfuegos, whose plane was lost in 1960. “Camilo had gone down in Macio Bay near Casilda in Trinidad. We saw an oil slick on the water and a fisherman told me, ‘that oil spot is a sign that a boat or a plane went down.’ We went back to Casilda and talked with Commander Pena, who was the uncle of this girl Dalia who was a very good underwater swimmer. She was tall, thin with very white skin and very beautiful. We took Dalia with us in the boat to have her dive and see if she could find the plane, but she didn’t find anything. Later we found a small pillow from Camilo's Cessna. When Fidel came to Trinidad, he was introduced to this girl and he fell in love and he took her back to Havana and nobody has ever seen her since. “

But Nancy Perez Crespo, born and raised in Trinidad and now living in Miami, was told that the couple had met in Havana. “Dalia’s father, who was called Quique, came from a very wealthy family who owned a cigarette factory in Trinidad. Quique married this woman Blanca who was low class in comparison with Quique’s family who were opposed to the marriage. They had two daughters and a son, Fernando, who was my good friend. When they were divorced, Blanca left for Havana with the two girls, Fernando lived with his father, grandmother and aunt Gloria in Trinidad. But the girls would come in the summer to Trinidad and for vacations. I remember Dalia as beautiful and blonde. She was dating a guy in my neighborhood, Tony Munoz, a doctor’s son who lives in New Jersey now.

“In 1964, I saw Fernando before I left Cuba. He came to say goodbye to me. He dreamed of leaving but he never could. He told me a secret he had just learned about. On a trip to Havana, his mother had told him, ‘your sister has a lover who is a very important figure in the Revolution and they have children,’ and Dalia wants you to see her sons. So he went to see Dalia but the street where she lived had what they called a frozen zone and nobody could pass by. And he got very suspicious. He finally made it in to the house and Dalia told him that her boyfriend was Fidel Castro. He was in shock.”

Although Dalia’s status remains a state secret, her existence has long been known among Castro’s inner circle. The late Jose Luis Llovio Menendez, a high ranking Cuban official who defected in 1982, recalled seeing Dalia often at Castro’s house, actually a compound, on 166 Street in Siboney. “We went to his home often for State meetings and sometimes to watch movies in his screening room with a big screen,” he said. “The security was always around but you couldn’t see them. There were three gates and it was well protected. I saw Dalia there but she and the children lived in another house nearby. I saw her there many times. We went there for meetings that were very confidential. Dalia was very polite but Fidel never introduced her as his wife only as ‘companera.’ He treated her like everyone else, no show of affection, nothing. But I knew that she was his wife just like everybody knew.”

**

Some Castro critics contend that the peculiar personal lifestyle of Fidel Castro has had deleterious consequences for the formerly cherished institution of the Cuban family. Castro haters point to Castro as a role model for the island’s moral woes. The obvious counter argument is that adultery is the norm for much of the hemisphere, hardly abated by the Catholic Church’s position on divorce. Nevertheless, the Cuban family has seen a dramatic breakdown since the Revolution. More than half of all couples divorce, many never marry, and infidelity is the national sport of the country. Cuba also has the highest rate of abortion and suicide in all of Latin America.

The fact that eight out of ten Cubans who defect are men has only augmented the staggering number of single mothers. If the Maximum Leader never created a role for a First Lady nor ever introduced his brood of children to the public, argue his critics, why should the ordinary Cuban be anymore deferential to women. Castro defends his position as a refusal to indulge in the celebritization of his family. "I've always been opposed to mixing politics and my personal life," he told one filmmaker. But having no family model has had its cost for the Cuban people. The coup de grace for Cuba's familial disaster has been the one million Cubans who have fled. It is the rare Cuban family which has emerged intact – on either side of the Florida Straits.

The Castro of Calle Ocho

Juanita Castro has lived in Miami since October 1964. A month earlier, she convinced her brothers that she wanted to visit their sister Emma and her family in Mexico City. Raul Castro, who has served as the family patriarch since their father’s death, arranged an exit visa for her. Once in Mexico, however, she denounced the revolution and - implicitly - her brothers. Salvador Lew, who had fled Havana two years earlier, handled her subsequent trip to Miami and public relations. “Juanita was a revolutionary. She fought Batista and she bought weapons for Castro,” said Lew, “but she felt betrayed because she saw that the communists were taking over the government. Fidel didn't want her to leave Cuba but they believed her story that she was going to live in Mexico with Emma.”

Lew waited at the Miami airport for Juanita’s plane, expecting a somewhat dowdy woman, based on photographs she had sent him. He was shocked when she stepped off the plane. “She was young and beautiful with dark hair, wearing sunglasses and beautiful legs,” he said. “I told her right away that we had already won. And she said, ‘why?’ And I said, ‘Because you're very beautiful.’ She's tough too. Just like her brothers. She has to be.”

I first met Juanita Castro at the pharmacy she owns on Miami’s Calle Ocho. She then drove us to a Coral Gables restaurant in her taupe Mercedes sedan. She is a woman with the recto carriage and bearing of her brother Fidel but the somewhat softer facial features of her younger brother Raul. At 71, she has been twice engaged but never married. In her narrow but tidy office in the rear of the drugstore are photographs of her family and the Pope. She bears the same devout faith of her mother, Lina, and wears a small gold cross. Her life has been difficult but she says she has no regrets. “If the same thing were to happen again,” she told me. “I would do it the same way.”

Juanita Castro’s bustling pharmacy is very successful and has made her a woman of means. But as one who was born to considerable wealth, there is nothing flamboyant about her or her Coral Gables home. A no-nonsense trim woman with auburn-tinted hair, she greeted me in slacks, a black blazer adorned with a handsome, understated gold pin. A trace of whimsy was evident in her leopard skin slipper shoes which she extolled for their comfort and her blue tinted eyeglasses.

Despite all the estrangements and byzantine complexity of her family, it remains the cornerstone of her existence. She is close to all her sisters, Emma in Mexico and Agustina, the youngest of the family at 64 and Angelita, who is now 79, in Havana. Although she has not spoken with her brothers since she left, she said she found the conventional wisdom about them baffling. “Everybody says Raul is the bad guy and Fidel is the good guy. But these are roles they took at the beginning of the Revolution. It’s not true - maybe the opposite. Raul was the favorite of my mother, and the favorite of mine because as I have said - he was very tender hearted. With the family he is very, very, good.”

Like her older brother, Juanita is not moved easily to forgiveness or surrender. Forty years have not cooled her ire with him for some intemperate comments he made about their father. “When the Revolution triumphed, Fidel said on a TV program that he was the son of a land owner, an exploiter,” she said with evident injury. “At the beginning he said that ‘all family ties are produced by virtue of pure animal instinct.’ He said this in regards to the family ties. Animal instinct not love! This is something that has troubled me.”

Juanita feels that her brother was less than a dutiful son to her beloved parents. “My father was very badly treated by Fidel at the very beginning of the Revolution. I never could forget this. Later, he wrote very well of my father. But what Fidel said about my father was not fair because my father was a very good man, a very generous person. He supported Fidel all the time, when he was in school and after school and when he got married to Mirta. If Fidel wanted a car, my father bought a car. Whatever Fidel wanted, he got. I remember once Fidel drove from Havana to Matanzas and crashed his car. And our father bought him another car.”

The Castro clan was a large one: three brothers, four sisters plus two half siblings, Lidia and Pedro Emilio, who were raised by the first wife but visited often. “When we were young, we all got along well and there were no problems,” recalled Juanita. “During vacations we were always together, we would go to the beach together with our mom. It was very pleasant. I have no bad memories from my childhood with respect to my brothers. The problems came later. Before the Revolution, Fidel was normal.” Juanita described her parents as caring without being outwardly expressive. “They were affectionate but nothing extraordinary outwardly,” she said. “Raul was closer to my mother and my father than Fidel, but Fidel was close too. Fidel was different -he didn’t show his feelings easily, he was very reserved. The personality of Fidel’s and my father’s are very similar. I remember my father as an austere, reserved, strong character and personality, and not especially expressive. Very gallego. My mother was more affectionate. My mother had more of a sense of humor and she liked to joke, to tell stories. But Fidel was distant from everybody. Fidel did everything on his own. He had his own ideas.”

Their father Angel Castro, who hailed from an impoverished family in Galicia, Spain, had come to the rough and wild backwoods of Oriente at the turn of the century seeking a better life. Juanita denies the claim of the Diaz-Balarts that her father had been a calvary soldier for the Spanish, but her brother Ramon says that their father came to Cuba as a "conscript" for the Spanish. What is certain is that Angel Castro worked ceaselessly and amassed one of the largest fincas - estates- in Oriente. “Our father was very dedicated to his work, - a formidable worker. He never rested,” recalled Juanita. “Every year he said he was going back to visit Galicia but he never did. He had a nephew and niece there and he helped them with money. My oldest sister, Angelita, took charge of writing letters and sending money to the relatives in Spain.”

Her mother’s family of seven children had hailed from the easternmost province of Pinar del Rio but had resettled in Camaguey, three fourth’s across the island, seeking better jobs. One maternal Castro aunt, Maria Isabel, in her late 80’s, still lives in Camaguey. Seeking to help her family make ends meet, a teenage Lina took work as a housekeeper at a large finca in Biran, about one hundred miles further west. It was not long before she attracted the interest of Angel Castro. Her son Fidel says often that his mop

Angel had been married to Maria Argota, a schoolteacher and the mother of his first two children, Lidia and Pedro Emilio. When and how he married Lina (who was the same age as his daughter Lidia), and how he disposed of Maria Argota is a subject of dispute. Some say the two families were initially raised together on the vast grounds of Angel’s holdings. It is commonly believed that Fidel, his brother Raul and his sister Angela were born out of wedlock and that it was some years later before Lina was able to convince her stubborn lover to submit to a church wedding. Some claim that Maria Argota died, others say Angel divorced her and that she moved away.

Some observers and historians contend that Castro’s illegitimacy marked him irrevocably. “Fidel Castro is the son of a servant with his father,” said Father Amado Llorente, Castro’s favorite high school teacher at the Belen School. “It is important to know this problem he had because in Spain and in Cuba they were too tough with these cases. So he hated society. He spoke to me about his mother not being the mother of the first two children of his father and this was difficult and complicated for him. Apparently, the first wife died from a psychological illness and that’s how Fidel’s mother and father began living together. But he is not completely illegitimate because later the Bishop of Santiago married his parents and baptized the children. Still, this was always a shadow over his life; he never could overcome it completely. More than once he said to me, ‘If I had not found you, I would say that I have no family.’”

However, the rough and tumble Mayari region where the Castro clan was raised had an elastic and unconventional moral code. Common law marriage was not unusual and often married couples would separate but never bother to divorce. Some of this is attributable to the iconic individualism found in the countryside but certainly the strictures of the Catholic Church played a part as well. Infidelity is as Cuban as sugarcane and for a period, Angel Castro juggled two families. Left to his druthers it is unlikely that the hardheaded Angel would have bothered with a church wedding or the baptism of his children.

Llorente agrees with Juanita Castro that Fidel was the father’s favorite. “His father was cold and tough, but was very proud of him because he knew he was the most intelligent of the children.” Jose Ignacio Rasco, a school friend from Belen, takes another view. “Don Angel was an old-fashioned Spaniard, a Gallego, who was a harsh man, with rude manners and very hard on his most rebellious son, Fidel.” Rasco and Llorente contend that Castro had a troubled relationship with his father. “He and his father had a bad time of it,” said Rasco. “He had a duel with his father on horseback because he said that he was defending the workers from his despotic father.”

But Juanita Castro asserts that such a rift never existed until after the Revolution. “No, he never fought with my father and was never upset with my father. They had good relations. My father was a straight shooter and good guy with very good feelings towards Fidel. My father financially supported Fidel all the time, when he was in school, after school and when he got married to Mirta.” Indeed, Luis Conte Aguero, a former close friend of Castro's and Orthodox party activist, recalled meeting Angel Castro in Havana shortly before his death in which the strong willed Gallego confided, "Fidel is my favorite son."

Unlike their older brother Ramon, nicknamed Mongo, a renowned mujeriego (skirtchaser), Juanita remembers her brother Fidel as being more subdued. ”I remember Fidel as being always very private. He didn’t brag and he was always very reserved about his personal issues. Mongo was the most amorous. It didn’t matter if they were married or single, Mongo went after them. Fidel was Mirta’s boyfriend and then they married very quickly.”

All the Castro siblings remained close through childhood and all were active in the Revolution. And with the exception of Juanita, who speaks only with her sisters, the family maintains its ties to each other, however strained at times. “Fidel sees and visits with my sisters - but on a totally familial level. They don’t get into politics,” Juanita explained. “The only one who stood against them and could not take what was happening was me. At the beginning, my mother supported the Revolution, of course. Later she had problems but she was their mother also. She used to joke about the situation. She was a woman with a great sense of humor and she would take things lightly. She worried about what was going on, but she always kept it to herself.” Juanita believes that her father, who dedicated his life to building his estate, would have taken an even dimmer view of his son’s Revolution.

Like her brother, Juanita can hold a grudge indefinitely. In 1955, when her brothers were released from prison only Raul returned home to visit with their parents in Biran. “My father had wanted Fidel to study, to begin his career as a lawyer, to become a good man. He always worried about him. When Fidel was a prisoner, dad suffered much during those two years. He never saw Fidel again. When Fidel got out of prison, Fidel didn’t go back to see my father but stayed in Havana. He promised to go but he never did. Raul went and spent a week with him. Fidel never went home. Then my father died one month before Fidel returned to Cuba in 1956.” The fact that her father never saw his favorite son before he died still troubles her.

But Juanita disputes those who claim that Castro did not visit their mother on her deathbed. “My mother died in my house in Miramar on 7th Avenue in 1963. It was a massive heart attack. She had circulation problems and already had suffered a heart attack before. One afternoon around 5 p.m., when she was finishing her bath she had a strong pain in her chest. We sent word immediately to Fidel and Raul and they came to my house as soon as they found out. There are people who say that Fidel didn’t come, but he was immediately at the house.”

However, Juanita felt that her brother gave short shrift to her mother’s burial. ”The whole family came to the burial except my sister Emma who was in Mexico. She came two days later. I can’t say how sad Fidel was but Raul was very affected by her death. He had been her favorite because he was so caring. From the moment Raul came to my house in Miramar, he was with us the whole time and traveled with us to Oriente by train. Fidel flew and met us at the train station.” His cursory visit to their home in Biran only worsened matters in her view. “She was very upset because Fidel was not caring enough about his mother when she died,” said her friend Salvador Lew. “He came into the place where his mother was laid out in Biran and did not stay long.”

Juanita’s view of Fidel as a less than dutiful son is confirmed by Castro’s former comrade, Lazaro Asencio who saw Lina Castro and her famous son at the end of 1959 at a rally outside the famous church near Santiago of La Caridad del Cobre, Cuba’s patron saint. “Lina was a great lady, a peasant woman and she was very religious,” said Asencio. “It was raining cats and dogs and Fidel didn’t take off his coat to give it to his mother. I had to take off my coat and give it to his mother. ”

Asencio noted that Castro family members had little immunity from the actions of their brother. Ramon Castro, who had always tended to the family finca and who took charge after their father’s death, found out quickly that his younger brother would be calling the shots. “Fidel called for Mongo to come and see him,” said Asencio. “We were friends and I saw him on the way in. I was there to see Juan Orca, Fidel’s secretary. When Ramon came out of his meeting with Fidel he told me, ‘Lazaro, I went in a rich man and I came out a poor man.’ Fidel had taken the family farm away from him.”

Asencio related another anecdote about Castro and his half-brother Pedro Emilio in early 1959. Following a television interview in 1959, Castro and Asencio went out for coffee at Calle 12 and 23rd.. “We sat down for our coffee and a soldier, the type of guy we called an "alcahuete," a fawning type, said ‘Fidel, look, Pedro Emilio is over there drinking,’” related Asencio. “Fidel stood up and went over to him and said, ‘Pedro Emilio, why are you wearing a 26 of July captain’s uniform when you never fought against Batista? And there’s an order that those in uniform cannot be out drinking?’ Pedro Emilio said, ‘So what! I’m not doing what you want. ’ Right then and there they took Pedro Emilio off to jail. That was astonishing to see.” Asencio quips that the only person to get a measure of revenge on Fidel Castro has been his infant son in 1952. “We used to live in Santa Clara by this highway on the outskirts, and Lazarito was about a year old and some months, and every time Fidel went by Santa Clara he would come to my house and eat with us. Back then we had cloth diapers and Lazarito was hot so he took off his diaper, and Fidel goes "Ay Lazaro, how beautiful is your son" and he picks up Lazarito who suddenly pisses all over Fidel.”

*

Like most exiles, Juanita copes with the complexities, secrets and anguish of being separated from her homeland and family. Nevertheless she remains generous and available to all visiting relatives and is especially close with her three sisters, Agustina and Angelita, the eldest, in Havana and Emma. “My sister Emma is very much like Fidel, physically. She has always gotten along well with Fidel and visits him a few times a year.

She’s not political, she leads a very private life in Mexico City with her husband, her daughter and son. “Emma likes Fidel very much,” says Lew. “Emma is not a Communist but she feels that he's a great person.” Emma’s daughter visits Juanita often and always spends Christmas with her. Ramon’s son has also visited Miami and his Aunt Juanita. But unlike many visiting Cubans, he chose to return home. Any of her brother Fidel's nine children or 8 grandchildren would be welcome in her home.

Two of Agustina’s sons have lived quietly and privately in central Florida since the mid-90’s, their identity unknown outside of the family. Juanita bemoaned the fact that Agustina had been unable to get a visa to visit them for so long. “She’s a woman who really loves her sons and worries about them,” says Juanita, her voice rising, “but she has to wait for a special permit to be allowed to travel here. You only see this in Cuba. If I want to go to China I go without having to ask for anybody’s permission. In Cuba, you have to wait till they do you the charity.”

In January 2001, Agustina, after nearly a year’s wait, finally received her travel visa. The Miami Castro clan, with Juanita as their matriarch, celebrated at her house. But as expected, Agustina returned to Havana six weeks later, bearing the conflict of many Cuban families. “She will miss her sons but she doesn’t want to leave her relatives in Cuba,” explained one friend. Unlike her sister Emma, Agustina is not close with Fidel.

The only relative whom Juanita has shut her doors to is Alina Fernandez, the illegitimate offspring of her brother and his short lived mistress, Naty Revuelta. When Fernandez fled Cuba in a theatrical exit - first to Madrid, then Miami, she availed herself of Juanita’s generosity. But after Fernandez penned a memoir which Juanita felt distorted and slandered her family, Juanita filed a lawsuit against her and her Spanish publisher. She even questions whether they share a bloodline. “Alina is not a good person. If you have a chance, ask Fidel if he is her father,” she says, “because he tells people that he is not.” It is true that Castro has never said that she was his daughter, but the special treatment she received in Cuba, belies the fact that he thinks otherwise. Juanita’s friends warned her that such a lawsuit could bankrupt her, to which Juanita responded, “Then so be it. I will serve my parents.” In December 2001, after three years of litigation, Juanita prevailed.

"Alina was a bit of a ding-dong," a State Department hand in Havana said of Fernandez before she fled. “She is a character.” Prior to her defection, Fernandez had endured a position in Cuba not unlike Billy Carter's during his brother’s Presidency. In a country at war with glitz and glamour, she had chosen to be a fashion model and had a series of sensational quickie marriages. One Castro insider said there had been little contact between Alina and Castro. "He never spoke to her," she said wryly. "That's why she became a dissident."

Among the issues in Fernandez’s irreverent and bitter memoir that disturbed Juanita Castro was her claim that Lina Ruz Castro was descended from Turkish Jews. Fernandez offers neither evidence nor sources to support her claim so it is impossible to verify. However, it is not unlikely that the ancestors of Castro’s father were Jewish. Angel Castro hailed from the northern town of Lugo in Galicia, an area in Spain where Jews traditionally lived and the Castro apellido is regarded as a Jewish name in Sephardic circles. Armando Castro, who says he is a distant cousin of Fidel’s asserts that “all the Castros in Oriente were Jews.” And in an interview with exile Bernardo Benes, in the mid 1980’s, Castro confided that the rumors were true. “He said to me, ‘As you know, I have Jewish ancestors,’ remembered Benes, who is a Cuban Jew. “I think it was on his father’s side. And he said he wanted Cuba to be a second Israel.” Castro’s rhetoric has been, on occasion, anti-Israel and within his inner circle, according to Llovio Menendez, Castro derided Israel and what he saw as the excessive influence of Jews in America. But his policies have been notably benign towards Jews. In 1993, he returned a synagogue in Santiago to its congregation and in 1998 he attended Hannukah services at the Patronato, the historic synagogue of Havana.

Fernandez’s book make reference to other illegitimate sires of Fidel Castro. One hatched from a three day liaison on a train trip to Oriente in 1949 and is named Jorge Angel Castro. All of Castro’s children, legitimate or not, have been economically provided with good homes, schools, and jobs. but Castro is not known for being much of a father. In a conversation with me in 1993, Castro declined to say how many children he had, but conceded, half in jest, “almost a tribe.” Lazaro Asencio claims Castro told him in 1961 that he had fathered more than fifteen children. I asked Castro in 1994 how many children he has. "Not that much. Less than a dozen," he paused, adding coyly, "I think."

Contrary to Fernandez’s account, she is not the only daughter of Fidel Castro. There is at least one other. Her name is Francisca Pupo known to her friends as Panchita, and she was born in 1953. She has lived quietly in Miami with her husband since 1998, when she won a lottery visa to leave Cuba and her father granted her an exit visa.

Lazaro Asencio remembered Francisca’s inauspicious beginnings. “After Batista’s coup, we all mobilized. I was president of the Las Villas University and Fidel was into the student’s struggle. He went to a rally in Cienfuegos in mid 1952 and they arrested him and took him to the jail in Santa Clara. Fidel sent for me and said, ‘Look Lazaro, I want your brother Pepe to defend me.’ Fidel was already a lawyer but could not practice because he had not yet been sworn in. In court, Fidel talked and talked until they shut him up. My brother as his lawyer spoke three or four words in his defense and the court let him go. “